In The Flow

Yegor Ostrov: In the Flow

Egor Ostrov’s style combines two inexhaustible sources of elegance: on the one hand, high tech; on the other, the aristocratism of European painting from the Renaissance to the modem age.

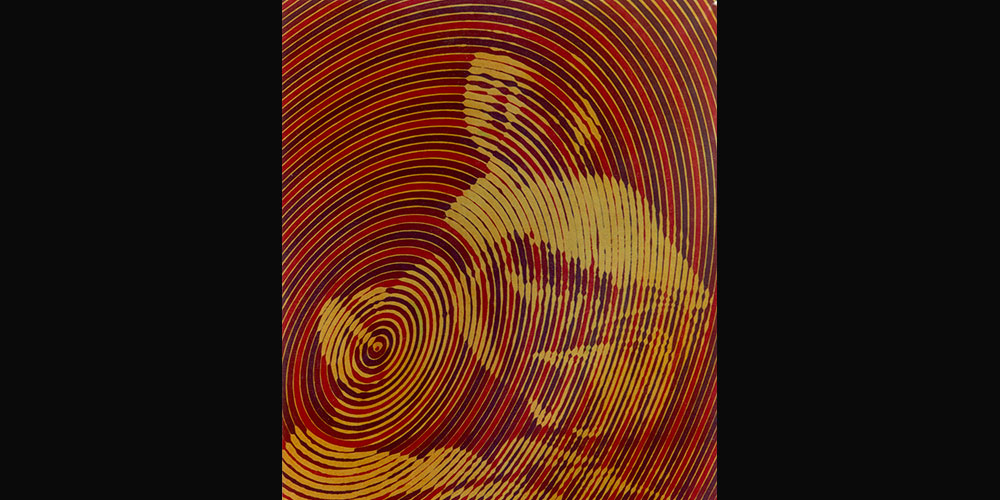

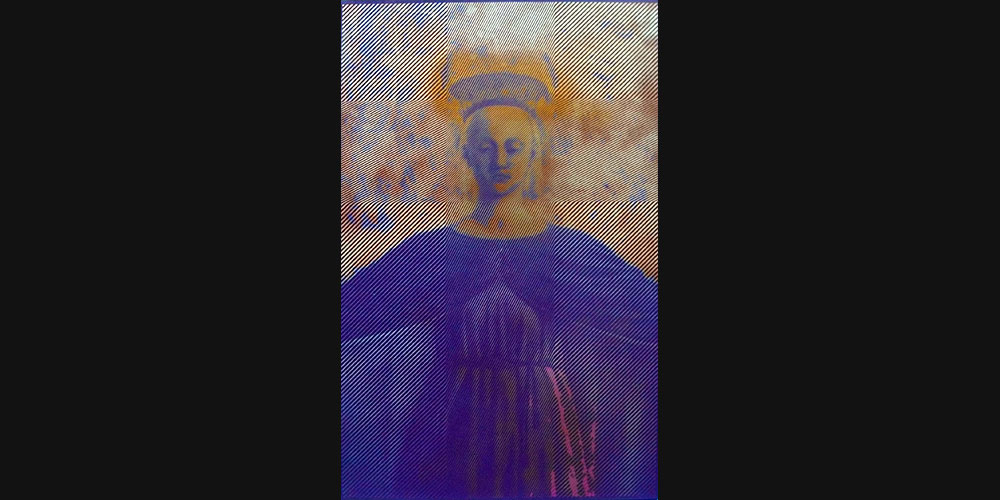

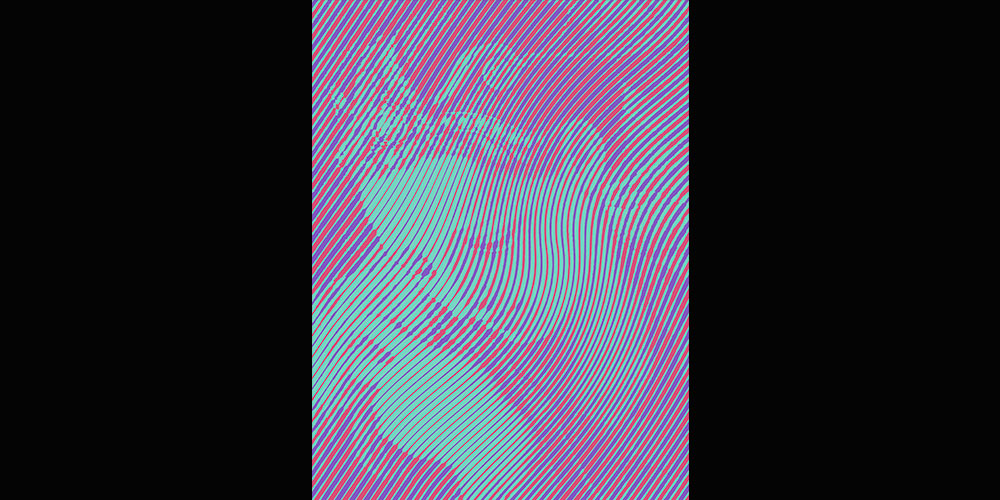

The designer’s brilliance on the surfaces of his reflector-like paintings, executed in acrylic or automobile paints, and often engraved on mirrors, gives way to the unearthly grandeur of the images bequeathed to us by Leonardo da Vinci, Bronzino, Mantegna, Ingres, and other geniuses.

However, classical painting and technology (the raster grid superimposed on the figurative image) encounter each other in an obvious and aggressive way. If you focus on the raster grid and view the work from close up, you will not be able to make out the artist’s figurative composition, but you merely have to step back and the grid disappears: the diagonal abstraction is no longer readable; one image as it were cancels the other. Ostrov examines how, at turn of the twenty-first century, the classical image exists in the harsh conditions of reproduction that define the current technological environment.

Ostrov demonstrates the iconicity of the classical image in modernity, and in this sense he is an heir to Andy Warhol, who inserted the Dove company logo into one of his series of takes on reproductions of Leonardo’s Last Supper. Warhol was hardly engaged in blasphemy; on the contrary, he wanted to recall the objective basis of symbolism, the real basis of all computed harmonies, for the dove on the soap pack or the Christian symbol of the Holy Spirit is the silhouette of a living bird, chosen to symbolize purity for the amazing, snowy color of its plumage. To the viewer of the eighties, when Warhol chose The Last Supper as his subject, the Dove dove , brought the news that we live in a global flow of images, where industrial trademarks intersect with masterpieces that have become their own trademarks. But, most importantly, there is, something that leads us precisely to these classical images from antiquity and the Renaissance: the intuition of immortality.

The intuition of immortality rests on the objectivity of beauty, which unites figurative and abstract art thanks to the universe’s physical perfection. Outside this law, geometry becomes a functional barcode that allows us to know almost everything about a particular thing but does not reveal how to breathe life into it. In a 1953 lecture entitled «The Question Concerning Technology», Martin Heidegger argued that modernity is characterized by a disastrous fission of the world into «bare» technology, which conceals technology’s essence, and «bare» aesthetics, which makes it impossible to sense the essence of art. He implied that both the functional approach, which ignores the idea of perfection, and abstract formalism destroy art — techne — the news of the power of beauty, which Plato ranked alongside immortality.

However, in mathematics — the basis of the latest technologies — the idea of beauty has not lost its significance: it is the beautiful solutions to problems that mathematicians consider the most effective. Ostrov is enthusiastically engaged with the latest physical and mathematical theory of the universe — string theory, which imagines the elementary particles of the universe as vibrating, closed or open strings. String theory enables one to visually express the «networked» connections among images of the world. It argues that chaos is only one of the states of a self-structuring, creative cosmos, the moment when certain forms dissolve and others emerge in the flow of a universe that endlessly rebuilds itself.

For twenty years, Ostrov has experimented with his compositional technique, which seemed at first to demonstrate the impossibility of a simple representation of the world. As the years have passed, Ostrov’s diagonal raster — a version of Pop artist Roy Lichtenstein’s Ben-Day dots, which symbolize the technological provenance of the modem visual image — has begun to serve a different notion of the artistic image. Ostrov’s vision has always been informed by a linearly structured picture of the world — the picture provided by European prints, etchings and engravings, which captured the creative worlds of the great artists with their networks of hatching lines. Ostrov has begun to see not only the image’s nerve-like graphic frame, but also to control its dynamics, extracting from the raster lines consonances or dissonances that emphasize the import of his compositions. Thus, the linear «smog» that absorbs or bifurcates the picture has been transformed into a new means of incarnating it in the present day. Ostrov’s «string section» combines the ancient voice of the Apollonian kithara with the latest electronic sound, just as cutting-edge string theory in physics reiterates the insights of the medieval mystics, who, like Honorius Augustodunensis, imagined the universe as a sonorous, harmoniously fashioned zither.

Ostrov’s paintings have turned into singular acts of disclosing the secret «nervous system»of classical and neoclassical painting and sculpture masterpieces. The classical image is austere and schematized, but essentially Ostrov has generated a scheme that ensures the reproduction of the basic semantic and figurative details. The glimmering of the painted surface imparts to these images a new technogenic, superhuman objectivity. They are incorporeal thanks to their reflective texture, but they are precisely objective and absolutely convincing as ideas of perfection.

Egor Ostrov acts as a translator of images from the symbolic language of classical art into the iconic language of today’s technological civilization. In modern parlance, his paintings «go with the flow» perfectly, that is, they contain the rhythm of constant global movement, the uninterrupted dynamic of change directed from the past into the future.

Ekaterina Andreeva